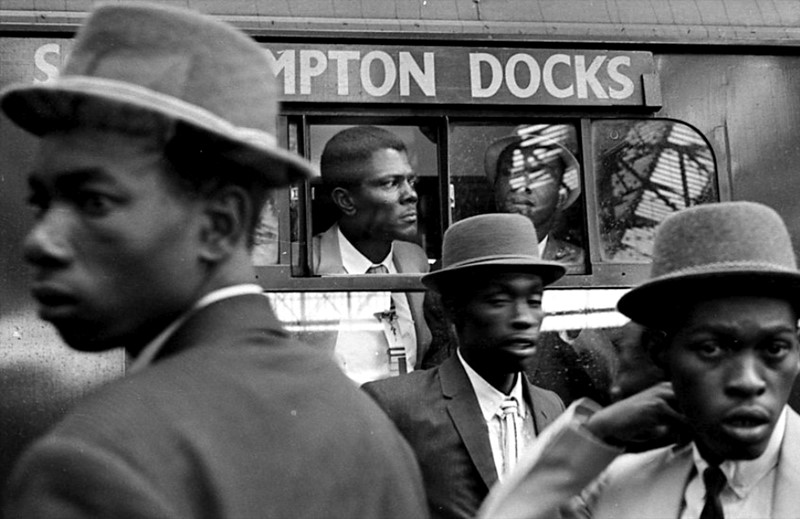

If a black man of a certain age talks to you of England, listen. If he speaks of the year 1955 you may be certain that he wasn’t born there because few blacks were in England then who hadn’t come from the sea. Watch his hands and his eyes. His hands will tell you things which his words can’t and his eyes will mask tears that won’t fall.

He’s of that generation who came with nothing but God and rum in their bellies and a desire for more.

If you ask him he’ll relive his first encounter with snow and ice and of fog in London, fog so thick that you couldn’t find your own house even though you might be standing right before it. “But then everything look so alike then, you couldn’t tell anyhow. That was England”

He’ll remember forever his first winter and his first job and the first English child who followed behind him in the street and begged him: “Please mister, can we see your tail? Me dad says all you wogs have tails. Come on then, please mister.” And his look of disappointment when you didn’t produce one.

He’ll remember too his first pub and the piss taste of English beer and his experimenting with all the strange drinks which faced you behind the counter until at last the wonder and discovery of Guinness which was dark and bitter like life itself and brought pleasure.

This was a time in Britain when even a banana was considered exotic because no one had ever eaten one (no one worth knowing anyway). And no one travelled more than fifty miles from where they were born except to go to war and the only blacks ever seen were in movies from America where they either danced with Shirley Temple or ran from Tarzan in the jungle. Or else they came as soldiers with the long war and everybody hated them because the English women found them strange fruit and exciting.

And so you went to work in darkness and returned home in darkness and in between was the pub and the fish and chips store, where they served the chips wrapped in newspaper and this was called a great treat and the ink was rumoured to kill germs.

What saved you during the day at the factory was the tea-time. Workers lived for that, and would strike for that if for nothing else. The one thing which reminded you really were human after all. You had your “Cuppa” and poured in as much sugar as possible for the energy boost it promised. Sugar which is the currency of our lives, for didn’t sugar make Britain? Wasn’t it King Sugar after all which brought us to the islands?

They’d ask you where you came from and if you answered Montserrat they would want to know what part of Jamaica that was. It didn’t matter. Sugar made you royal, sugar and sea-island cotton. So that kings could eat from plates of gold and drink from crystal. Montserrat, so tiny an island in the Caribbean and yet 20,000 a year could die there annually during slavery and be replaced.

History formed us and maybe the very same firms of ship owners who landed us in the Caribbean now brought us to England only now it was called immigration and we get to pay for that privilege. And what was it that kept us sane for all those years of labour in the 50s doing those jobs which the English didn’t want to do because of danger or class or pride or skill? Those years when it went from: “ Rooms to rent, no Coloureds or Irish or Dogs need apply” to harassment on the shop floor and no union to appeal to because they’d write the word “Troublesome” on your work card and that would seal your fate. No one would hire you. You either kept your mouth shut or quit. No shop steward was going to take your side over an Englishman.

On the streets there were the Teddy Boys with their hob nail boots and bicycle chains and they‘d chase you into alley ways. The Teddy Boys tried to dress and wear their hair like Elvis Pressley. Oswald Mosley was a Tory MP who started the British Fascist Party and supported Hitler during the war. He loved to stir things up. The Teddy Boys acted as his Storm Troopers. On Saturdays you had to stay off the streets because football meant you were in trouble regardless to which side won the match. Drunk with anger or celebration it didn’t matter, you were always a target of the mob.

It was in 1958 that things finally reached a breakpoint and the Notting Hill riot happened. They came expecting an easy skirmish, the usual breakage followed by taunts of “Go back where you came from!”

What they encountered instead was a major battle. They hadn’t planned on blacks who had served in the war as soldiers preparing their homes for a siege. Blood ran in the street and the Teddy Boys were soundly beaten. It was only then that the police acted and the wagons arrived, carting people away. The defence of Notting Hill had been well planned and caught the intruders totally unprepared. It was a major turning point for race relations and Britain would never be the same again. Now things were said out loud which were only said in whispers. The Labour party was forced to take a stand and promise that if it won it would put in place the first Anti-discrimination Act in Britain although it would take another six years to arrive. By then blacks had stopped apologizing for existence.

The most baffling thing about blacks in Britain is that for the most part they had no intention of staying originally. Although many had been asked to come through recruitment campaigns in the islands which said Britain needed workers after the war, those who came never planned to stay. Most had a five year plan. It was in fact the vicious prejudice they encountered which made them refuse to be beaten. The reflex response was fierce resistance. It was only later that you came to realize: “My God, it’s here I live now.”

And what was it that kept you whole during all those years of draught and wonder? Was it family and friends sent for from back home and who only arrived one by one and fragment by fragment? The women who came and kneaded you like cassava bread? Yes. And the sanity which came and could only come from the music which raised you up. You must keep it close no matter what the struggle outside. Keep the cadence and the cadence keeps you and holds the harm away.

“Bring me me food in a calabash calabash

Bring me me food in a calabash

Bring me me food in a calabash, calabash

Me no want no food in no bowl.”

When a black man of a certain age talks to you of England, listen. Watch his hands and then his eyes for they’ll pierce you and tell you the things his words never can. Hear him.

Note: Edgar Nksosi White is a novelist and playwright. His novel, The Rising, is available on Amazon.