It’s a curious thing about the Caribbean. We will acknowledge genius but never quite forgive it. I used to say this about Montserrat but I’ve come to see that this is a fault of the Caribbean as a whole. It’s only that it’s more noticeable on a small island. Now, this can be genius in anything; it doesn’t matter. The question then becomes:

“Why he and not me? How did he become so strong?”

This is more easily excusable in sports where if someone excels, they can at least say:

“Well, is he father teach he. Is the father he come from.”

When it comes to the arts, genius is not so forgivable. It is usually met with:

“If I had the time, I would do that but I too busy. I have responsibilities.”

Which translates to, genius is just having too much free time on your hands.

Jealousy in the Caribbean isn’t limited only to Sports and the Arts. It works equally well for anyone who comes up with an original idea. Anything out of the ordinary will get you labelled different and left. The cliché is always the way to go, and the first choice, whether it has to do with tourism or Church. A good West Indian never lets a platitude go unused. The contradiction of the Caribbean is that while it claims to love culture, it has no love for the people who create culture.

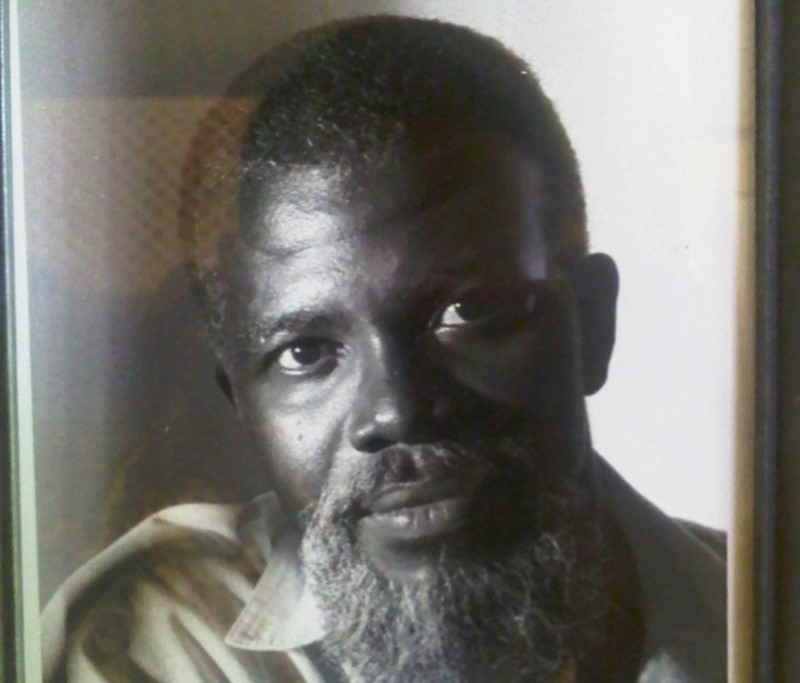

Into this strange paradox was born one Earl Warner in Christ Church, Barbados. He was born in 1952 and graduated secondary school in 1969, which was three years after Barbados’ Independence and a good time for youth to flex muscles. This is around the period when they were still debating whether dialect was a legitimate language and whether it should be taught in schools. Prior to this, dialect had been beaten out of us against the tamarind tree. Out of this clash of experience comes theatre. What starts out as calypso and skits and once-a-week soirees in rich expats’ homes, eventually becomes theatre. Drama is an active word meaning to do and make happen.

Earl Warner found he liked the stage, where he could make things happen. And he liked making things happen anywhere, even on a street corner. He would improvise situations with a partner named Clifford. Take this skit:

Two men in the jungle: one named Cap And Hand, the next named Hopes. Cap And Hand goes to give God back some water and while he’s leaking he gets bit by this snake on his penis. He bawls out:

“Hopes, run quick go get the doctor, tell he where the snake bite me.”

So Hopes goes and finds the doctor but the doctor is busy delivering a baby. He tells Hopes that he’s going to have to go back and suck the poison out himself. So, Hopes goes back and Cap And Hand says:

“Where the doctor, what he say?”

Hopes takes one look at him and says:

“Boy, doctor say you go have fu dead, friend!”

From this early comedy skit came the desire to do more, make people laugh and think at the same time.

Desire and talent are two of the three elements necessary to do theatre. The third is exposure. You never really know what you’ve got until you step out of the grave which is Regionalism. In 1972 there was a pivotal occurrence in the Caribbean: CARIFESTA (Caribbean Festival of Arts), a major inter-island arts festival. For the first time, groups from different islands were able to interact with each other. The cost of interisland travel is so prohibitive that we are still as colonially divided as in the 18th century, but for one startling moment, CARIFESTA broke down the walls. Groups from all over the Caribbean were asked to attend and perform. The one major theme seemed to be the thirst for identity. “Are we more than just post-colonial subjects?” was the question everyone seemed to be asking. There were groups from Jamaica and Trinidad and of course, Guyana, which was the host and had a lot of history and past to celebrate.

There were many currents in the air at that time (the ‘70s). There was Castro and his ability to both raise literacy rates in Cuba and also produce the finest doctors in the Caribbean while at the same time, surviving U.S. attempts to erase him by embargo and assassination. There was the last gasps of Black Nationalism (which had been all but destroyed in America but was alive and well in the Caribbean. There was also the radical theatre of Grotowski, (the so called “Theatre of Poverty”) and the off-Broadway Black Theatre. All of this filtered through the Caribbean by way of tourism and the diaspora and perhaps, the first generation of young people who could afford to discover roots in the Caribbean. There was money moving around freely. There was even a production of Dutchman by LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), a play which is set entirely in a New York subway.

All of this had a profound effect on Earl Warner. He found that he not only loved performing but directing as well. Now the search was on for material which he could bring to life. Writers like Derek Walcott and George Lamming were some twenty years older. Warner would eventually direct their work but first he wanted to get his own vision clear. He travelled and studied and earned a degree in theatre from the University of Manchester in England. There he was bombarded by images, not only of theatre but what life in England was like compared to what he had been taught in Barbados, which was proud to be known as Little England. But what happens when the England of reality conflicts with the England of the mind? Disillusionment or a stubborn refusal to surrender the expectations. This is why you have so many West Indians of a certain age still running around wearing suits regardless of whatever work they have to do, be it cleaner or clerk.

Warner came back knowing exactly what he wanted to do with theatre as well as where he wanted to do it: the Caribbean. He studied theatre-craft well enough to produce whatever effect he wanted on an audience. The audience he knew and loved best.

He was able to work both in Barbados and Jamaica. Jamaica, especially, was important because of the availability of the Jamaica School of Drama as well as the adjoining School of Dance. This opened up tremendous possibilities. Here he could both study and collaborate with others like Dennis Scott who was teaching as well as directing and writing. Warner learned a great deal from Dennis Scott and I think the appreciation was mutual. Scott saw all the possibility in Warner. Dennis liked to use symbols in the architecture of the stage (a vision which came to him from dance which he participated in for many years as a principal dancer in the Jamaica National Dance Company). Warner took this a bit further. He founds objects and listened to their story and then made that part of the play.

The only fly in the ointment to all this creativity was the reality of Jamaica itself and the fact that it had become like the Wild West. Guns were everywhere and so was crime and political shootouts. The only thing to do was to become so involved in theatre that you might avoid a bullet, especially at election time. The School of Drama (located near Half Way Tree in Kingston) became a sanctuary, an inviolable space where lesser spirits like Death wouldn’t enter; you hoped.

But let’s take a look at Jamaica in the ‘70s, pulsing with music and violence. Michael Norman Manley was no more in power. He had been spanked by the U.S. and by the Jamaican middle-class who found that he was getting too much like Castro or too much like Marcus Garvey when Manley started giving land to the poor. A major rule of the Caribbean is: who have power keep power. Land is power so you don’t part with that and above all, you keep it in your class if not your family. You let others work it but you make sure you keep it. So what you do with a Manley is you take your money out the country and see what he could do then. He’ll have to go begging (cap in hand), probably to the IMF or the World Bank and they will be sure to put him under manners:

“Take off that bush jacket Mister Manley, and put on a suit if you want our money, oh, and you have to scale back on that free lunch foolishness and land redistribution.”

Anyway Manley is out and Edward Seaga is in and now gunfire is the soundtrack of our lives. It’s hard to ask people to leave their barricades to come and see theatre, but ask you do and they come. Warner, now with a series of successes attached to his name, had to make a decision: Whether to take this theatre thing seriously or to go into the corporate world and do theatre as a hobby on weekends and summers. He could earn a very good living in or out of the Caribbean as an accountant. He had skill and background in that area too and he could play the part well. Accountancy for Warner meant argyle socks. It was part of the corporate uniform of the period. It symbolized everything he hated about the West Indian middleclass. Warner found that he couldn’t just turn creativity on and off in the 8 to 4 world of the Tourism Office or keep his madness confined to weekends.

He felt sorry for the middleclass in Jamaica who had to live trapped in their gated communities with armed guards who were themselves the most likely to rob you. He refused to ever live like that. This is why Gordon Town (an oasis just outside of Kingston) was so important to Earl. He wanted to earn enough to be able to remain in the Caribbean and not have to be forced into exile. The answer for him was mobility. Mounting and directing plays for several different groups at the same time all over the region. Now he was able to deal with Walcott’s work and make theatre adaptations of writers like Earl Lovelace (The Dragon Can’t Dance) and George Lamming (In the Castle of my Skin) and give to them both what they never had in the novel versions, tempo pace and music.

Earl was a genius when it came to opening up space in a text and creating a total theatre of movement and music and drama all happening simultaneously. He had a core group of actors he could depend on as well as venues and companies that would plead for his assistance. Now, it had all come together, an audience, actors and writers who he could work with and challenge. Another avenue that suddenly opened for him was television. It seemed like a perfect fit, the Jamaica Television network meets man with ideas. However, there is a reason why television people are television people and not theatre. Warner explained it to me like this:

“Television people sit down to work and theatre people stand up. That’s why television people are so anal. All them so, must have haemorrhoids, trust me. And they wear argyle socks!”

Television is always a government agency, unlike theatre. Television delights in mediocrity; it even takes pride in it. Its policy is that you can never go wrong if you shoot for the lowest denominator of audience intelligence. Those are the shows which run the longest and those artists who either write for or direct them, work the longest and are able to support both mistresses and trophy wives. Needless to say, Earl didn’t do very much television directing.

Now the curious thing about the Caribbean attitude to genius is that it’s forgivable in the young. The child prodigy is always cute and forgivable for we know with certainty that life will soon put an end to all that success. The child who excels in music or wins spelling B competitions can be patted on the head and placed back in the box until called upon again to amuse or entertain. When it becomes no longer cute, is when adulthood reaches and you’re regarded with suspicion and called a loose cannon because as the Haitian proverb says:

“Trop lespri sot pas lwen” (Where there’s too much genius madness isn’t far away).

So to get back to theatre, Earl had to learn how to manoeuvre the various minefields of the Caribbean, how to refuse no reasonable offers and yet stay relevant. Earl liked to mingle with people from both sides of the divide so that he never lost touch with what was reality. In other words, not spend so much time among the radicals that you actually believed the rhetoric of billboards and slogans about change and prosperity. Fortunately, if you had friends on both sides of the aisle, one of them might warn you in time when they’re coming after you to shut your dream down.

Another aspect of the Caribbean fear of genius is the attitude to women of talent. Not even the Church likes women with too much ability and of course, the society takes its cue from the Church. Women have to literally fight their way to the altar to be pastors. Every denomination has its excuse for why this is. The ideal role of the woman is to be the support system of the male Pastor who is usually the senior. The paradox is that the majority of churches are comprised of over eighty per cent women and children. It is, in fact, the women who cause the men to come. The Civil Service itself is a mirror image of the Church. Women in authority are usually allocated glorified secretarial positions seldom with real power. And to complete the irony the strongest critic of women in authority in the Caribbean is other women.

“Is who she thinks she is anyhow? She talks so fast, is like she having orgasm.”

“I wonder if she even know what that be.”

Reacting to all this, Warner went out of his way to seek out intelligent actresses (he even married one, Karen Ford) and gave them space to tell their story. He was very good with women in general. He inspired confidence and certainty even when everything was falling apart, a very necessary ability in a director. He knew that trust is infectious.

He wondered why so few Caribbean playwrights could write good parts for women. Or bothered to. Not Walcott or the writers, Lamming or Lovelace. So Warner went the improvisation route and had women create from their experiences and write their own parts. The result of this was work with the Sistren Collective (in 1989) who took the stage to the community and reached another level of theatre. Among some of the women key to the realisation of this vision were Pat Cumper and Honor Ford Smith. Earl was the first guest male director of this group which had started since 1977. Later they would adapt Buss Out which was a seminal theatre piece. The Jamaica School of Drama was a mecca for all the experimentation and cross fertilization to use a term which Rex Nettleford loved to use; but it was accurate. By putting together a collection of actors, teachers and set designers from all over the Caribbean, it was possible to do through art what it proved impossible to do in politics: create a federation. It soon became evident that there was such a thing as a Caribbean style and sensibility which was unique and worthy of pride. Every island has an African presence regardless of all attempts to erase it. There is such a thing as a Caribbean style of storytelling. For example we never like to say something directly. “Me no call no names.” We prefer innuendo. It’s very much like climbing a steep hill. We never walk in a straight line we prefer the zigzag motion of a drunken man because this method makes the ground appear level and therefore is less tiring.

Because Warner was able to both live and work in Jamaica he was given access to a core of actors with whom he was able to form a close bond and who he could depend on, a central core of artists and technicians who would find a way to realise whatever ideas he had bouncing in his mind. It was truly a lab and he was never too proud to accept a suggestion if he found it better than his own. The urgency was always how can we best tell a story and bring it to life for someone who never set foot in a theatre before? How do we capture imagination?

As a result of his investigation into the conditions of women in the Caribbean he had to take the next step and deal with the psyche of the Caribbean man as regards to his role in society. This is a dangerous area because this is where all fears are hidden. When a man feels powerless, he has to beat on something and his woman is the closest thing (even closer than himself) so he beats on her instead. Given the fact that Jamaica, where Earl was based, has the reputation of being the most macho island in the Caribbean (no other island is known for stoning to death homosexuals in the street), violence and rituals of manhood are played out daily in the streets and houses. Every sexual encounter with women is a contest and man must always conquer and force her to orgasm or else retreat in defeat. One of the two must surrender first. (Interestingly, there are far fewer rapes in the Caribbean than in Africa or India). In the midst of all this manhood talk though is a lot of hypocrisy.

After all is said and done, it still comes down to race and class and money. For example, although homosexuals may be stoned if they are poor and black, someone like Noel Coward who was a white Englishman and an entertainer could come to Jamaica with all his American money and English proclivities and run wild in Montego Bay and he would be in no danger whatsoever. If anything, he could be assured of complete police protection and government blessing. As long as the money last. For the black poor, manhood is the only possession: Manhood, not defined in property or wealth but a sense of where you belonged in a hostile universe and a society which measured your worth only in terms of potential for labour. A sugarcane economy, which basically has not changed in three hundred years. What your father did, you do and what he didn’t own you will probably never own.

Earl found that the major force for change and self-image in Jamaica and the Caribbean as a whole was Rastafarianism. It changed the society from the bottom up and marked the difference between the conscious man and the unconscious. Given the harsh origin of the Rasta movement in Jamaica starting from the 1930s enduring police invasion and imprisonment in both jails and mental institutions, the movement has somehow managed to transform not only Jamaican society but Caribbean society as a whole.

Reggae is a worldwide phenomenon influencing even Africa and the Far East and how did it do this? By taking America and then Europe. Given the hostility which Reggae music met in Jamaica, to the extent that it was hardly played on the air waves (which was saturated with American Pop and Country Western), it’s amazing how the message still got through. When I was in Iraq, the music I heard most was Reggae, Bob Marley’s Rat Race. Through the music everyone was stopping long enough to question. Questions are dangerous things. In the Caribbean, prior to the sixties no one had time to question anything. We moved as animals move. This was the way of things. You didn’t question government, police and certainly above all you didn’t question God.

This was the thing that fascinated Earl Warner, the way people just followed. Twelve families ruled Jamaica. Sugar estates became rum estates like Appleton refineries. You either worked for sugar or for rum. In the 70s they had you working with bauxite. But you can’t own it like land you work it. And because you can’t drink bauxite you drink rum. And in the corner of your bed is your woman but you can’t help but wonder would she still be if you had no job, no bauxite. These are the thoughts that go through a man’s mind sometimes. He worries about the things he cares about so he trains himself not to care. From these reflections and others, Warner put together a theatre piece called Man Talk. The title makes you think of the infinite mystery surrounding those two words and what it felt like as a child to be excluded from such conversation and how badly you wished and waited for the day when you finally would be allowed entrance into that inner sanctum which is manhood. Never knowing at the time that this world has more to do with what is never said than what is. The silences. You ambush pain while it’s still love and before it becomes pain.

Man Talk was a breakthrough for Earl. Each work just helped him to refine his technique and sharpen the lens he saw through. He was able to use the best from his success in one arena and transfer it to another. He more and more relied on the opening up of the text and employing simultaneous time and levels of action. For example, instead of merely watching one scene at a time, we may witness three scenes taking place at the same time on different levels of the stage. In other words, life doesn’t necessarily await our big scene or event, it happens all around us and in fact never stops happening. To make this work dramatically you need an ensemble of actors who can both interact and improvise while at the same time listening very carefully and intently to all that’s happening around them. Being aware like musicians in an orchestra who complement each other and not upstage what the other is doing. Controlled rapture. He was able to do this best with his Theatre Company Limited (TCL) group which were the best and most senior of his ensembles. They consisted of those who he had worked with the longest: Marina Taitt, Harclyde Walcott, Alwin Bully, and Owen Ellis. They were best able to translate his style of theatre.

Earl Warner was uniquely placed in time and place. He was able to absorb the best in theatre because he was able to travel to Europe and America and work, as well as maintaining a base in the centre of the Caribbean at a dynamic period (the 1970s - 1990s). The Jamaica School of Drama was an excellent place to begin an apprenticeship which would later become his own recruitment centre. The Jamaica School of Drama would go on to become the greatest single influence on Eastern Caribbean theatre. Through Derek Walcott and Dennis Scott, Earl Warner’s work was seen at the Eugene O Neill Centre in America and he became a member of a highly prestigious pool of directors who could choose where and when he wanted to work. He could so easily have ended up teaching at Yale Drama School had he chosen to. He preferred to stay in the Caribbean.

We often spoke about how the Caribbean chooses to deal with unusual talent. They either choose to ignore it (hoping it will pass), or else throw prizes at it and name things after it. The thinking being: “Well that’s dealt with, now go away.” He understood the mentality perfectly but he always said that although he knew that it was mostly guilt and hypocrisy which caused them to honour any Caribbean artist or hero (Earl had directed my play, I Marcus Garvey) and we talked about the way that after shutting out Garvey while he was alive, they dug up his remains from an unmarked grave in London and returned him not only back to Jamaica but used his image on the currency.

“Honours should be accepted not for us but for those coming after. They have to see the possibility of the impossible.”

Earl had a unique gift. He knew what he wanted and was willing to take a chance on himself and his dreams. The problem he faced is the same one encountered by anyone attempting to do anything different or innovative in the Caribbean: the distrust of genius. There is a genuine fear of anyone on a mission or anyone with too much of a sense of purpose. Most men go to theatre for the same reason as they attend church, i.e. their women ask them to. As a result, they already enter defensively. They don’t want to hear anything about the nature of the soul or the story of several generations of incest and child abuse on a family. The first thing they’re going to say is:

“Man, you hitting me hard!”

They want something light with a few tunes, a few girls on stage and an excuse for a little whining. Something to make them feel they had a night out. Any story in between is an extra. Warner’s gift was his ability to present a mirror of the society, entertain and yet provoke. He lived his work while others just kept their jobs.

One of the last projects which we were working on together was a play on Don Drummond, the Jamaican musician who was an acknowledged genius on the Jazz trombone. He was known as the High Priest of Ska music. His career ended tragically when he killed his girlfriend and ended his life in an asylum. Warner saw so much more than just the music. Earl saw Don Drummond as part of the identity crisis which followed after Independence in the 1960s.

We had done so much research on the period, the Alpha Boys School where Drummond was raised as an orphan, and the conscious choice which Drummond made to refuse to take medication because it interfered with his creativity (and his sex drive). I even interviewed the psychiatrist who attended to Drummond at the Bellevue Asylum in Kingston. I had the perfect actor, Basil Wallace who resembled Drummond. All the parts were coming together when Warner took sick. I never realised just how ill he was because he refused to slacken his pace and he had so many obligations to fulfil and people he didn’t want to disappoint. You can leave your job; you can’t leave your work.

The last image I had of Warner was him having to lie down while he directed. I suppose he would have directed from his hospital bed if he had to. What I remember most is his laughter. He had come to terms with things I never knew about. He was still doing the thing he was born to do. He had worked with some of the best writers and actors that came out of the period (1960-90). He was unique in that he was acknowledged early and was able to communicate his vision with others.

In the end, he is one of the few Caribbean artists who fulfilled his potential and did not end mad, suicidal or forced into argyle socks. He gave love and inspiration to all those who knew him and received it in equal measure from his wife, children and theatre family. This is a very far cry from the generation before him, all of whom, were driven into exile in either America or Britain and who mostly died in lonely rooms with scripts and unfinished manuscripts gathering dust or else staging Old Story Time for tourists on weekends in some school auditorium.

Warner didn’t have to face the pain of exile. Yet, he always contended that the West Indian as an entity is in exile even in his own country. And why? Because he barely dares to know himself. Warner was blessed in that his life’s work was finding that self. The day I heard he died I remember that it was a long sunset and that the clouds bent low and close like a thief or an old woman begging. I felt alone. But I wasn’t.

Note: Edgar Nkosi White is an Editorial Contributor with MNI Alive Media