In 1976, Gerald A. Sypitkowski, an off-duty police officer, was shot in the head and killed during an attempted robbery outside a Detroit bar. Witnesses, including Sypitkowski’s partner, said the shooter was in a white Lincoln Mark IV, which was registered to Leslie Nathanial, reportedly a local loan shark.

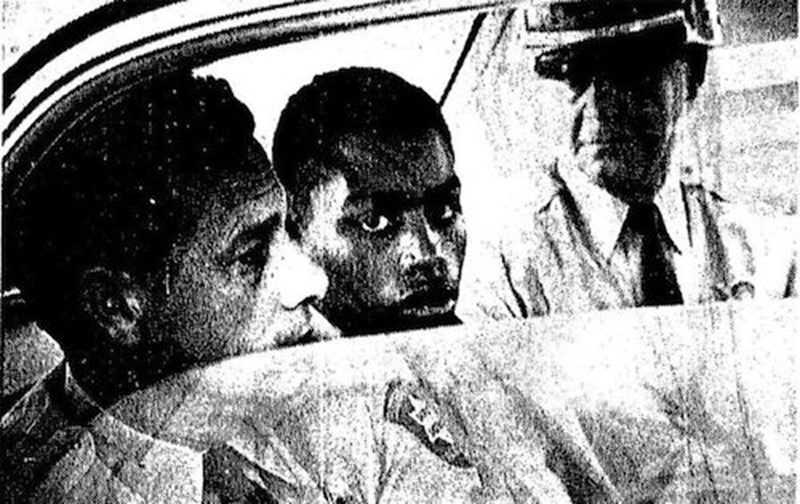

Four teenagers, including 17-year-old Charles Lewis, were later arrested. In a deal brokered with the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office, three of the teenagers agreed to testify that Lewis had shot Sypitkowski while riding in the back seat of a yellow Gran Torino, rather than the white Lincoln that was reported by several witnesses. Over the course of two trials (the first one was dismissed), Lewis’s lawyer, M. Arthur Arduin (now deceased), failed to call any alibi witnesses for Lewis. Apart from the three other teenagers arrested, none of the eyewitnesses claimed that a yellow car had been involved in the crime. Lewis has repeatedly insisted that he asked the judge to remove Arduin as his lawyer and had his request denied. He also says that during his opening arguments, Arduin described him as “part of a gang” skilled at stealing cars. At his second trial, Lewis was convicted of first-degree murder and received a mandatory sentence as a juvenile of life without parole (JLWOP). Not yet out of his teens, Lewis would be spending the rest of his life in prison.

After the Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that JLWOP sentences should be given only in cases of “irreparable corruption,” Lewis applied for a resentencing. But as he began preparing for court, he discovered that his case file was missing. Judge Qiana Lillard ordered the two sides to figure out a way to reconstruct the file. According to Nicholas Bennett, Lewis’s new defense attorney, this was unprecedented; he argues that Lewis’s conviction should be dismissed outright, since the prosecution cannot verify any facts from the trial itself. While it’s not clear what happened to the file, the defense has asserted in court documents that the boxes of papers were misplaced at the clerk’s office and possibly destroyed to prevent the county prosecutor’s office from reexamining the case. The current county prosecutor is Kym Worthy; her office has publicly admitted that a number of case files were destroyed in 1995 by her predecessor.

To complicate matters even further, there’s a document from 2000—one with its own docket entry—stating that Lewis’s conviction had been overturned. Since the court record is missing and was likely destroyed, there is no way to determine if this order is legitimate. (The prosecutor argued, and a judge agreed, that the order was forged, because “it just doesn’t add up.”) The same problem will apply to all of the other documents, Bennett says.