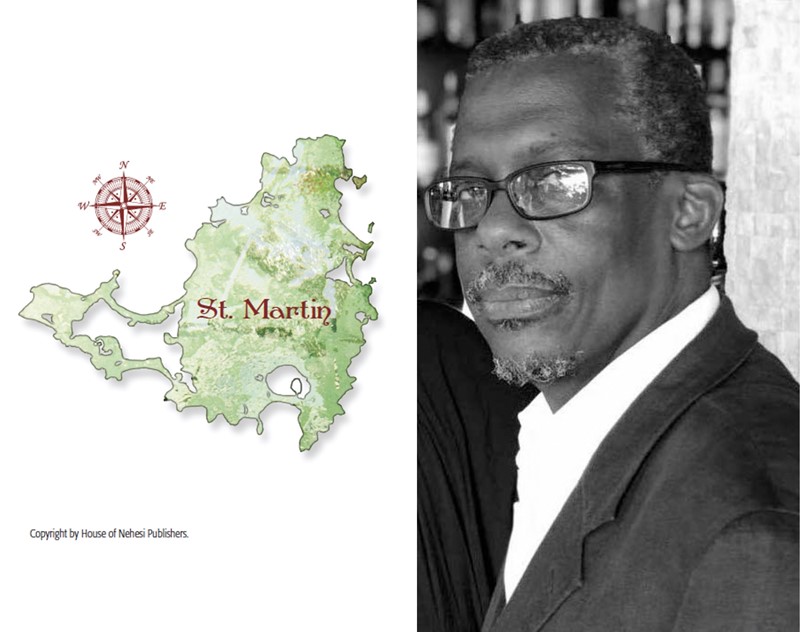

The Treaty of Concordia, or Partition Treaty, purportedly signed on March 23, 1648, divided the Caribbean island of St. Martin between French and Dutch imperial, slaveholding, and colonial interests.

According to articles 5 and 6 of the Treaty of Concordia, most of the people, the enslaved African people of St. Martin, were, based on the French and Dutch laws of the day, property of the European slave owners.

The Black people were neither the “inhabitants” nor the “persons” referred to in what was significantly a business agreement to facilitate the exploitation of the salt and other material resources (art 5) in the two colonial territories.

That the enslaved people would have been ordered to pick, carry, and pile the stones that marked the supposed spot on the Concordia hill where the treaty was said to have been signed, may be explored as legend or as our actual lot.

Such an exercise could be done with the same power that we pursue critical knowledge of the merciless, unreparated labor in the great ponds, building of the fortifications, mansions and mills, and the hewing, hauling, sowing, picking, and harvesting on plantations and from the salt marshes by our ancestors, driven as beasts under the slavers’ lash.

Know about the Concordia treaty as a historical marker, yes; but beyond that it might best be left as a simple historical curiosity, along the same lines as Peter Stuyvesant losing part of his right leg during his being part of the Dutch military leadership of the 1644 attack on the Spanish occupiers of St. Martin.

The Treaty of Concordia is not a festive day for the emancipated St. Martin nation.

And how would this accord be maintained as a “national” day in an independent St. Martin—beyond the current adjusted autonomy authorized by France and the Netherlands respectively in 2007 and 2010 for the North and South of our island?

The Treaty of Concordia is neither a founding text nor a seminal constitution of the truly liberated St. Martin nation. To our humanity this would be unmanly and detestable; and the French and Dutch nationality cannot absolve or solve what is the inherent evil at the very cornerstone of the Treaty of Concordia, and that is the dehumanization of the African or Black people of St. Martin as expressed, reinforced, and never corrected in that European accord.

The Partition Treaty of 1648 is not a thing of love, nor a celebration of the unity that was nurtured and consolidated most during the Traditional Period (1848-1963) by the people, individuals and families of the villages and towns of the St. Martin nation.

The Concordia treaty is not the foundation of this fraternal and familial unity of the St. Martin nation; a unity whose indivisibility we should be duty bound to honor, live, and fight for if needs be; a unity that is invariably forged best by all of the people—past, present, and the evolving future—of the South and North of our beloved Caribbean island, which is in the 21st century still a colony, by various names, of the Dutch Kingdom and the French Republic.

Editor’s note: The above is an abstract from an unfinished paper. © 2013, 2021 by Lasana M. Sekou, a St. Martin writer.