There Is No Superiority Of Caribbean Culture Over African American Culture

Growing up in a neighborhood of mixed Caribbean heritage, I noticed that there were strong biases and presumptions against black Americans and their communities. My Caribbean elders and my peers of second generation Caribbean Americans felt a sense of superiority to the so called "black American", meaning blacks who were descendants of the enslaved Africans brought to this country to be the free labor force that built this great country. One day, however, it occurred to me that as Caribbeans, we were not indigenous to our respective islands. Even though we boast having a richer culture than our African American peers we too underwent the evils of African enslavement in the Americas.

I began to wonder how that has since influenced us culturally and mentally, but also if we were more or less affected than our brothers and sisters who suffered here. I found that while slave culture in the Caribbean created a fusion culture of African tradition with European influence, it also led to negative consequences that are still present in Caribbean society today that are similar to the consequences faced by black American slave descendants. While it is clear that there was a divergence of cultural development between Caribbeans and African Americans, there is still a great deal of shared struggle that we can coalesce on. As a 2nd generation Caribbean American, I was raised with the foolish notion that being Caribbean automatically made me more culturally rich than black Americans. We have our own food, language, customs, and our entire government was black. We are sure of ourselves and we created and maintained an identity that was strong. But is it?

From my experiences, Caribbeans seems to believe we are of an identity that is purely our own, without much influence, as opposed to Americans who we view as having a watered down culture. However, this independent, richer culture is not without external influence. Some of us recognize our ties to Africa while others don't realize how their everyday lives and tradition have been passed down over generations since before we arrived in the West Indies. Rightly so, we are proud and boastful of our culture, but it is time that we started looking more critically at how our identity was molded. While the spirit of the people is truly African, the culture was definitely influenced greatly by slavery and colonialism.

Slave rebels fought their enslavers tooth and nail to retain African identity. Even after enslaved Africans in the Caribbean were freed, they refused to work for former slave owners. The heartbeat of the African, the drums, was forbidden in those times but African slaves resisted this ban and maintained the musical culture that influences our modern signature music today. Reggae, soca and other genres indigenous to the West Indies were born out of the beats and influences of our African ancestors. Even remnants of African religion survives today amongst the islands. To name a few, there is still some semblance of Shango in Trinidad and Cuba; Voodun in Haiti, Cuba, Puerto Rico and Dominican Republic, Cumina in Jamaica and Jankanoo in Jamaica & St. Kitts. Our Caribbean slave and freed ancestors were adamant about not losing their cultural pride and caving into the oppressors' negative view of us.

In Haiti, post-emancipation griots missioned to erase negative images of Africans portrayed by the Europeans. They told stories that glorified our ancestors and painted us in the light of heroes. Even African language has been retained in some forms over the course of time, but has been infused with slave-owner language to create uniquely Caribbean languages such as Creole, Patois and Papiamento. Without the severe onslaught of character and human worth that American slaves experienced to a greater degree than Caribbean slaves, our ancestors were sometimes able to resist and fortify their culture against the attacks.

However, despite our attempts to hold on to our traditions from our African roots, we are no more above the effects of slavery and oppression than our African American counterparts. One of the biggest emerging challenges to our sense of self as blacks in the Caribbean is colorism. I constantly ask myself how in countries that have an overwhelming majority black population, people can look in the mirror and believe that lighter skin is superior. Skin bleaching is reaching epidemic proportions in the Caribbean, as well as Africa, as many blacks there are rejecting their dark skin and viewing it as an impediment on their beauty or success. In addition to this warped sense of self-image that is becoming more pervasive, there is also a campaign of creolisation, the making inferior of a subculture, that takes place. While it its great that the languages and religions of our ancestors have survived in part over generations, there are many who believe that these cultural identifiers should be demoted to second-class status and even forgotten. Many view the language of the colonizers the Queen's English, French and Spanish as the languages the citizens must perfect in order to achieve. Instead of embracing the notion that the two can co-exist, there are advocates on both sides who either want to abolish the subsidiary languages or preserve it in the historical archives.

This sends a conflicting message to second generations, like me, who are constantly trying to connect with the so-called inferior aspects of the culture that we view as the most authentic. For example, I enjoy the small amounts of patois I am able to conjure up when around my family and take great interest in learning the folk customs that I miss out on by being in America. I think that this results from many Caribbeans not having to face race identity until they come to America, and thus they do not know how to discuss it candidly and recognize its negative effects. We sometimes come from islands, and then move to American neighborhoods that are homogenous that we never really have to face how all slavery and oppression has also had a large impact on our culture and is a great part of our identity as a people.

After all of this soul searching, I am at a place now where I can view American and Caribbean struggles as one in the same, with a few minor differences, and I can respect the greater struggle and transcendence that our African American relatives had to undergo to even get to where they are today. Knowing this, how can I possibly view myself as superior, in any way, to my own people? We have had different paths, but we are working towards the same goal. I can't forget that I too am a descendent of slavery, something that I notice many second generations immigrants seem to like to exempt themselves from. I call upon myself now to continue to absorb as much of the two cultures as I possibly can, while also working to defend against the negative affronts on our culture that threaten our very identity.

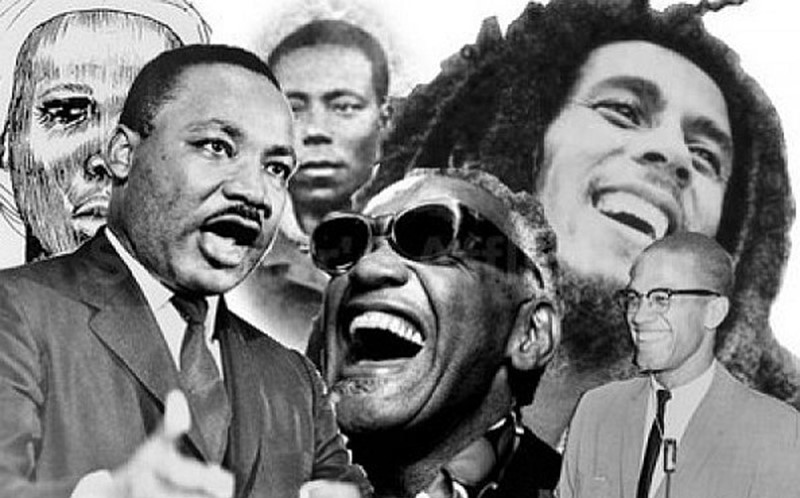

Photo Credit To Born Free Press

Editor-in-Chief's Note: Alicia Davis is an Editorial Contributor with the MNI Alive Network